4 Exploratory Data Analysis

The greatest value of a picture is when it forces us to notice what we never expected.

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) is a foundational stage of data analysis in which analysts actively interrogate data to understand its structure, quality, and underlying patterns. Rather than serving merely as a preliminary step, EDA directly informs analytical decisions by revealing unexpected behavior, identifying anomalies, and suggesting promising directions for further investigation. In the Data Science Workflow (see Figure 2.3), EDA forms the conceptual bridge between Data Preparation (Chapter 3) and Data Setup for Modeling (Chapter 6), ensuring that modeling choices are grounded in empirical evidence rather than assumptions.

Unlike formal hypothesis testing, EDA is inherently flexible and iterative. It encourages curiosity, experimentation, and repeated refinement of questions as insights emerge. Some exploratory paths will highlight meaningful structure in the data, while others may expose data quality issues or confirm that certain variables carry little information. Through this process, analysts develop intuition about the data, assess which features are likely to be informative, and refine the scope of subsequent analysis. The goal of EDA is not to validate theories but to generate insight. Summary statistics, exploratory visualizations, and correlation measures offer an initial map of the data landscape, although apparent patterns should be interpreted cautiously and not mistaken for causal relationships. Formal tools for statistical inference, introduced in Chapter 5, build on this exploratory foundation.

EDA also plays a central role in diagnosing and improving data quality. Missing values, extreme observations, inconsistent formats, and redundant features often become apparent only through systematic exploration. Identifying such issues early helps prevent misleading results and supports the development of reliable and interpretable models. The choice of exploratory techniques depends on both the nature of the data and the analytical questions of interest. Histograms and box plots provide insight into distributions, while scatter plots and correlation matrices help uncover relationships and potential dependencies among variables. Together, these tools allow analysts to move forward with a clearer understanding of what the data can, and cannot, support.

What This Chapter Covers

This chapter provides a structured introduction to exploratory data analysis, focusing on how summary statistics and visual techniques can be used to understand feature distributions, identify anomalies, and explore relationships within data. You will learn how correlation analysis helps detect redundancy among predictors and how multivariate exploration reveals patterns that support informed modeling decisions.

The chapter begins with EDA as Data Storytelling, which highlights the importance of communicating exploratory findings clearly and in context. This is followed by Key Objectives and Guiding Questions for EDA, where the main goals of exploration are translated into practical questions that guide a systematic analytical process.

These concepts are then applied in a detailed case study using the churn dataset from the liver package. This example demonstrates how exploratory techniques uncover meaningful customer patterns, how visualizations support interpretation, and how EDA prepares data for subsequent classification tasks, including k-nearest neighbours modeling in Chapter 7.

The chapter concludes with a comprehensive set of exercises and hands-on projects based on two additional real-world datasets (bank and churn_mlc, also from the liver package). These activities reinforce exploratory skills and establish continuity with later chapters, including the neural network case study presented in Chapter 12.

4.1 EDA as Data Storytelling

Exploratory data analysis is not only a technical process for uncovering patterns, but also a way of making sense of data through structured interpretation. While EDA reveals structure, anomalies, and relationships, these findings gain analytical value only when they are considered in context and connected to meaningful questions. In this sense, data storytelling is an integral part of exploration: it transforms raw observations into insight by linking evidence, interpretation, and purpose.

Effective storytelling in data science weaves together analytical results, domain knowledge, and visual clarity. Rather than presenting statistics or plots in isolation, strong exploratory analysis connects each finding to a broader narrative about the data-generating process. Whether the audience consists of analysts, business stakeholders, or policymakers, the aim is to communicate what matters, why it matters, and how it informs subsequent decisions.

visualization plays a central role in this process. Summary statistics provide a compact overview of central tendency and variability, but visual displays make patterns and irregularities more apparent. Scatter plots and correlation matrices help reveal relationships among numerical features, while histograms, box plots, and categorical visualizations clarify distributions, skewness, and group differences. Selecting appropriate visual tools strengthens both analytical reasoning and interpretability.

Storytelling through data is widely used across domains, including business analytics, journalism, public policy, and scientific research. A well-known example is Hans Rosling’s TED Talk New insights on poverty, in which decades of demographic and economic data are presented in a clear and engaging manner. Figure 4.1 visualises changes in GDP per capita and life expectancy across world regions from 1950 to 2019. The figure is generated using the gapminder dataset from the liver package and visualised with the ggplot2 package. Although drawn from global development data, the same principles of exploratory analysis apply when examining customer behavior, financial trends, or service outcomes.

Figure 4.1 reveals several broad patterns that emerge through exploratory visualization. Across all regions, both GDP per capita and life expectancy increase substantially between 1950 and 2019, indicating a strong association between economic development and population health. This trend is particularly pronounced for Western countries, which display consistently higher levels of both variables and a more pronounced upward shift over time. Other regions show more gradual improvement and greater dispersion, reflecting heterogeneous development trajectories. While these patterns are descriptive rather than causal, they illustrate how exploratory visualization helps surface broad global trends.

As you conduct EDA, it is therefore useful to ask not only what the data shows, but also why those patterns are relevant. Which findings warrant further investigation? How might they inform modeling choices, challenge assumptions, or guide decision-making? Framing exploration in narrative terms helps ensure that EDA remains purposeful rather than purely descriptive, grounded in the real-world questions that motivate the analysis.

The next section builds on these ideas by introducing the key objectives and guiding questions that structure effective exploratory analysis. Together, they provide a flexible yet systematic foundation for the detailed EDA of customer churn that follows.

4.2 Objectives and Guiding Questions for EDA

A useful starting point is to clarify what exploratory analysis is designed to accomplish. At its core, EDA seeks to understand the structure of the data, including feature types, value ranges, missing entries, and possible anomalies. It examines how individual features are distributed, identifying central tendencies, variation, and skewness. It investigates how features relate to one another, revealing associations, dependencies, or interactions that may later contribute to predictive models. It also detects patterns and outliers that might indicate errors, unusual subgroups, or emerging signals worth investigating further.

These objectives form the foundation for effective Modeling. They help analysts refine which features deserve emphasis, anticipate potential challenges, and identify early insights that can guide the direction of later stages in the workflow.

Exploration becomes more productive when guided by focused questions. These questions can be grouped broadly into those concerning individual features and those concerning relationships among features. When examining features one at a time, the guiding questions ask what each feature reveals on its own, how it is distributed, whether missing values follow a particular pattern, and whether any irregularities stand out. Histograms, box plots, and summary statistics are familiar tools for answering such questions.

When shifting to relationships among features, the focus moves to how predictors relate to the target, whether any features are strongly correlated, whether redundancies or interactions might influence Modeling, and how categorical and numerical features combine to reveal structure. Scatter plots, grouped visualizations, and correlation matrices help reveal these patterns and support thoughtful feature selection.

A recurring challenge, especially for students, is choosing which plots or techniques best suit different types of data. Table 4.1 summarizes commonly used exploratory objectives alongside appropriate analytical tools. It serves as a practical reference when deciding how to approach unfamiliar datasets or new analytical questions.

| Objective | Data.Type | Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Examine a feature’s distribution | Numerical | Histogram, box plot, density plot, summary statistics |

| Summarize a categorical feature | Categorical | Bar chart, frequency table |

| Identify outliers | Numerical | Box plot, histogram |

| Detect missing data patterns | Any | Summary statistics, missingness maps |

| Explore the relationship between two numerical features | Numerical & Numerical | Scatter plot, correlation coefficient |

| Compare a numerical feature across groups | Numerical & Categorical | Box plot, grouped bar chart, violin plot |

| Analyze interactions between two categorical features | Categorical & Categorical | Stacked bar chart, mosaic plot, contingency table |

| Assess correlation among multiple numerical features | Multiple Numerical | Correlation matrix, scatterplot matrix |

By aligning objectives with guiding questions and appropriate methods, EDA becomes more than a routine diagnostic stage. It becomes a strategic component of the workflow that enhances data quality, informs feature construction, and lays the groundwork for effective Modeling.

The next section applies these principles through a detailed EDA of customer churn, showing how statistical summaries, visual tools, and domain understanding can uncover patterns that support predictive analysis.

4.3 EDA in Practice: The churn Dataset

Exploratory data analysis (EDA) is most informative when it is grounded in real data and motivated by practical questions. In this section, we illustrate the exploratory process using the churn dataset, which contains demographic, behavioral, and financial information about customers, along with a binary indicator of whether a customer has churned by closing their credit card account. The goal is to understand which patterns and characteristics are associated with customer attrition and how these insights can guide subsequent analysis.

This walkthrough follows the logic of the Data Science Workflow introduced in Chapter 2. We begin by briefly revisiting problem understanding and data preparation to establish the business context and examine the structure of the dataset. The core of the section focuses on exploratory data analysis, where summary statistics, visualizations, and guiding questions are used to investigate relationships between customer characteristics and churn outcomes.

The insights developed through this exploratory analysis form the foundation for later stages of the workflow. They inform how the data are prepared for Modeling in Chapter 6, support the construction of predictive models using k-nearest neighbours in Chapter 7, and motivate the evaluation strategies discussed in Chapter 8. Taken together, these stages demonstrate how careful exploratory analysis strengthens understanding and supports well-grounded analytical decisions.

4.3.1 Problem Understanding for the churn Dataset

A bank manager has become increasingly concerned about a growing number of customers closing their credit card accounts. Understanding why customers leave, and anticipating which customers are at greater risk of doing so, has become a strategic priority. Reliable churn prediction would allow the bank to intervene proactively, for example by adjusting services or offering targeted incentives to retain valuable clients.

Customer churn is a persistent challenge in subscription-based industries such as banking, telecommunications, and streaming services. Retaining existing customers is typically more cost-effective than acquiring new ones, which makes identifying the drivers of churn an important analytical objective. From a business perspective, this problem naturally leads to three central questions:

- Why are customers choosing to leave?

- Which behavioral or demographic characteristics are associated with higher churn risk?

- How can these insights inform strategies designed to improve customer retention?

Exploratory data analysis provides an initial foundation for addressing these questions. By examining distributions, group differences, and relationships among features, EDA helps uncover early signals associated with churn. These exploratory insights support a deeper understanding of how customer attributes and behaviors interact and help narrow the focus for subsequent modeling efforts.

In Chapter 7, a k-nearest neighbours (kNN) model will be developed to predict customer churn. Before such a model can be constructed, it is essential to understand the structure of the churn dataset, the types of features it contains, and the patterns they exhibit. The next subsection therefore examines the dataset in detail to establish this foundational understanding.

4.3.2 Overview of the churn Dataset

Before conducting visual or statistical exploration, it is important to understand the dataset used throughout this chapter. The churn dataset, available in the liver package, serves as a realistic case study for applying exploratory data analysis. It contains combined demographic information, account characteristics, credit usage, and customer interaction metrics. The key feature of interest is churn, which indicates whether a customer has closed a credit card account (“yes”) or remained active (“no”). This binary outcome will later serve as the target feature for the classification model in Chapter 7. At this stage, the goal is to understand the structure, content, and quality of the data surrounding this outcome. To load and inspect the dataset, run:

library(liver)

data(churn)

str(churn)

'data.frame': 10127 obs. of 21 variables:

$ customer_ID : int 768805383 818770008 713982108 769911858 709106358 713061558 810347208 818906208 710930508 719661558 ...

$ age : int 45 49 51 40 40 44 51 32 37 48 ...

$ gender : Factor w/ 2 levels "female","male": 2 1 2 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 ...

$ education : Factor w/ 7 levels "uneducated","highschool",..: 2 4 4 2 1 4 7 2 1 4 ...

$ marital : Factor w/ 4 levels "married","single",..: 1 2 1 4 1 1 1 4 2 2 ...

$ income : Factor w/ 6 levels "<40K","40K-60K",..: 3 1 4 1 3 2 5 3 3 4 ...

$ card_category : Factor w/ 4 levels "blue","silver",..: 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 2 1 1 ...

$ dependent_count : int 3 5 3 4 3 2 4 0 3 2 ...

$ months_on_book : int 39 44 36 34 21 36 46 27 36 36 ...

$ relationship_count : int 5 6 4 3 5 3 6 2 5 6 ...

$ months_inactive : int 1 1 1 4 1 1 1 2 2 3 ...

$ contacts_count_12 : int 3 2 0 1 0 2 3 2 0 3 ...

$ credit_limit : num 12691 8256 3418 3313 4716 ...

$ revolving_balance : int 777 864 0 2517 0 1247 2264 1396 2517 1677 ...

$ available_credit : num 11914 7392 3418 796 4716 ...

$ transaction_amount_12: int 1144 1291 1887 1171 816 1088 1330 1538 1350 1441 ...

$ transaction_count_12 : int 42 33 20 20 28 24 31 36 24 32 ...

$ ratio_amount_Q4_Q1 : num 1.33 1.54 2.59 1.41 2.17 ...

$ ratio_count_Q4_Q1 : num 1.62 3.71 2.33 2.33 2.5 ...

$ utilization_ratio : num 0.061 0.105 0 0.76 0 0.311 0.066 0.048 0.113 0.144 ...

$ churn : Factor w/ 2 levels "yes","no": 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 ...The dataset is stored as a data.frame with 10127 observations and 21 features. The predictors consist of both numerical and categorical features that describe customer demographics, spending behavior, credit management, and engagement with the bank. Eight features are categorical (gender, education, marital, income, card_category, churn, and two grouping identifiers), while the remaining features are numerical. The categorical features represent demographic or qualitative groupings, and the numerical features capture continuous measures such as credit limits, transaction amounts, and utilization ratios. This distinction guides the choice of summary and visualization techniques used later in the chapter. A structured overview of the features is provided below:

customer_ID: Unique identifier for each account holder.age: Age of the customer, in years.gender: Gender of the account holder.education: Highest educational qualification.marital: Marital status.income: Annual income bracket.card_category: Credit card type (blue, silver, gold, platinum).dependent_count: Number of dependents.months_on_book: Tenure with the bank, in months.relationship_count: Number of products held by the customer.months_inactive: Number of inactive months in the past 12 months.contacts_count_12: Number of customer service contacts in the past 12 months.credit_limit: Total credit card limit.revolving_balance: Current revolving balance.available_credit: Unused portion of the credit limit, calculated ascredit_limit - revolving_balance.transaction_amount_12: Total transaction amount in the past 12 months.transaction_count_12: Total number of transactions in the past 12 months.ratio_amount_Q4_Q1: Ratio of total transaction amount in the fourth quarter to that in the first quarter.ratio_count_Q4_Q1: Ratio of total transaction count in the fourth quarter to that in the first quarter.utilization_ratio: Credit utilization ratio, defined asrevolving_balance / credit_limit.churn: Whether the account was closed (“yes”) or remained active (“no”).

A first quantitative impression of the dataset can be obtained with:

summary(churn)

customer_ID age gender education marital income card_category

Min. :708082083 Min. :26.00 female:5358 uneducated :1487 married :4687 <40K :3561 blue :9436

1st Qu.:713036770 1st Qu.:41.00 male :4769 highschool :2013 single :3943 40K-60K :1790 silver : 555

Median :717926358 Median :46.00 college :1013 divorced: 748 60K-80K :1402 gold : 116

Mean :739177606 Mean :46.33 graduate :3128 unknown : 749 80K-120K:1535 platinum: 20

3rd Qu.:773143533 3rd Qu.:52.00 post-graduate: 516 >120K : 727

Max. :828343083 Max. :73.00 doctorate : 451 unknown :1112

unknown :1519

dependent_count months_on_book relationship_count months_inactive contacts_count_12 credit_limit revolving_balance

Min. :0.000 Min. :13.00 Min. :1.000 Min. :0.000 Min. :0.000 Min. : 1438 Min. : 0

1st Qu.:1.000 1st Qu.:31.00 1st Qu.:3.000 1st Qu.:2.000 1st Qu.:2.000 1st Qu.: 2555 1st Qu.: 359

Median :2.000 Median :36.00 Median :4.000 Median :2.000 Median :2.000 Median : 4549 Median :1276

Mean :2.346 Mean :35.93 Mean :3.813 Mean :2.341 Mean :2.455 Mean : 8632 Mean :1163

3rd Qu.:3.000 3rd Qu.:40.00 3rd Qu.:5.000 3rd Qu.:3.000 3rd Qu.:3.000 3rd Qu.:11068 3rd Qu.:1784

Max. :5.000 Max. :56.00 Max. :6.000 Max. :6.000 Max. :6.000 Max. :34516 Max. :2517

available_credit transaction_amount_12 transaction_count_12 ratio_amount_Q4_Q1 ratio_count_Q4_Q1 utilization_ratio

Min. : 3 Min. : 510 Min. : 10.00 Min. :0.0000 Min. :0.0000 Min. :0.0000

1st Qu.: 1324 1st Qu.: 2156 1st Qu.: 45.00 1st Qu.:0.6310 1st Qu.:0.5820 1st Qu.:0.0230

Median : 3474 Median : 3899 Median : 67.00 Median :0.7360 Median :0.7020 Median :0.1760

Mean : 7469 Mean : 4404 Mean : 64.86 Mean :0.7599 Mean :0.7122 Mean :0.2749

3rd Qu.: 9859 3rd Qu.: 4741 3rd Qu.: 81.00 3rd Qu.:0.8590 3rd Qu.:0.8180 3rd Qu.:0.5030

Max. :34516 Max. :18484 Max. :139.00 Max. :3.3970 Max. :3.7140 Max. :0.9990

churn

yes:1627

no :8500

The summary statistics reveal several broad patterns:

Demographics and tenure: Customers are primarily middle-aged, with an average age of about 46 years, and have held their accounts for approximately three years.

Credit behavior: Credit limits vary widely around an average of roughly 8,600 dollars. Available credit closely mirrors the credit limit, and utilization ratios range from very low to very high, indicating a mix of conservative and heavy users.

Transaction activity: Customers complete about 65 transactions per year on average, with total annual spending near 4,400 dollars. The upper quartile contains high spenders whose behavior may influence churn.

behavioral changes: Quarterly spending ratios show a slight decline from the first to the fourth quarter for many customers, although some increase their spending.

Categorical features: Females form a slight majority. Education levels are concentrated in the college and graduate categories, and income tends to fall in lower brackets. Most customers hold blue cards, which reflects typical portfolio distributions.

These descriptive patterns illustrate the heterogeneity of the customer base and suggest that several numerical features may require scaling or transformation. Some categorical features, particularly education, marital, and income, contain an “unknown” category that represents missing information. Handling these cases is an important preparatory step.

The next subsection focuses on preparing the dataset for exploration by addressing missing values, verifying feature types, and ensuring consistent formats. Proper preparation ensures that the insights drawn from exploratory data analysis are both valid and interpretable.

4.3.3 Data Preparation for the churn Dataset

Before conducting exploratory data analysis, we carry out a limited amount of data preparation to ensure that summaries and visualisations accurately reflect the underlying data. An initial inspection of the churn dataset reveals that several categorical features (education, income, and marital) contain missing entries encoded as the string “unknown”. These placeholders must be converted to standard missing values so that they are handled correctly during exploration.

To standardise the representation of missing values, we replace all occurrences of “unknown” with NA and remove unused factor levels:

churn[churn == "unknown"] <- NA

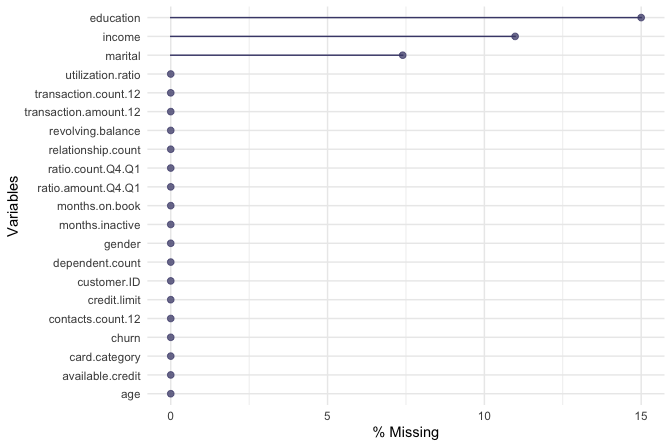

churn <- droplevels(churn)Before deciding how to handle the missing values, we assess their extent. The naniar package provides convenient tools for visualising missingness across features. The function gg_miss_var() displays the proportion of missing observations for each variable:

library(naniar)

gg_miss_var(churn, show_pct = TRUE)

The plot shows that missing values are confined to three categorical features, with the highest proportion occurring in education (approximately 15%). Strategies for handling missing categorical data are discussed in detail in Chapter 3.9. For the purposes of exploratory analysis, we apply random imputation to preserve the observed distribution of each feature and avoid distorting group comparisons. We therefore apply random imputation using the impute() function from the Hmisc package:

library(Hmisc)

churn$education <- impute(churn$education, "random")

churn$income <- impute(churn$income, "random")

churn$marital <- impute(churn$marital, "random")With missing values addressed and feature types confirmed, the dataset is now suitable for exploratory analysis. In the next section, we apply visual and numerical tools to uncover patterns associated with customer churn.

4.4 Exploring Categorical Features

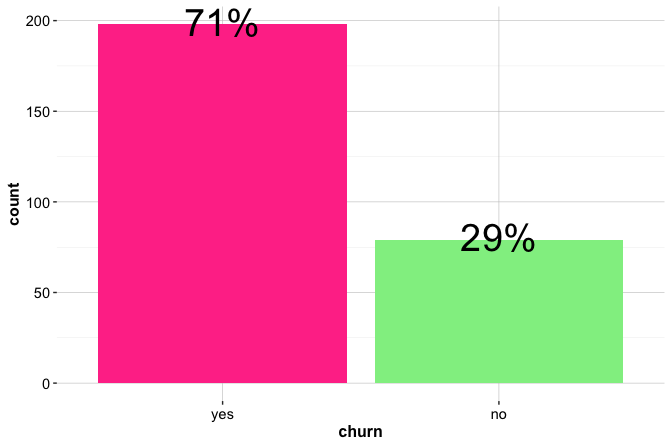

Categorical features group observations into distinct classes and often capture key demographic or behavioral characteristics. In the churn dataset, such features include gender, education, marital, card_category, and the outcome variable churn. Examining how these features are distributed, and how they relate to customer churn, provides an initial understanding of customer retention and disengagement.

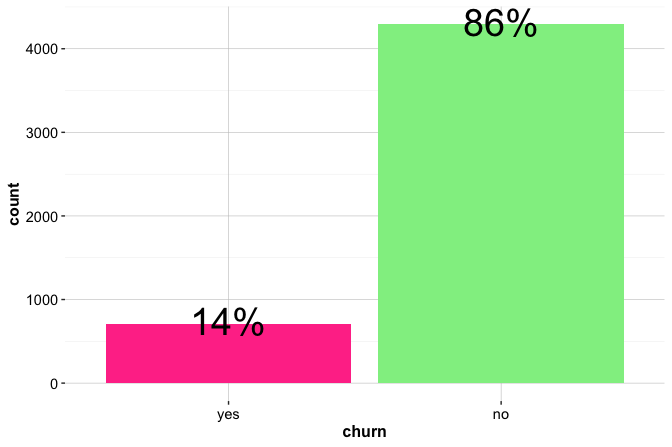

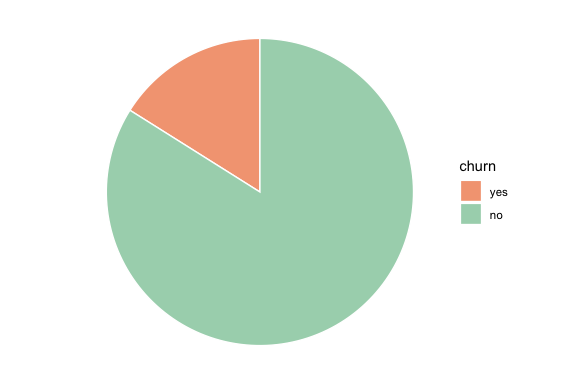

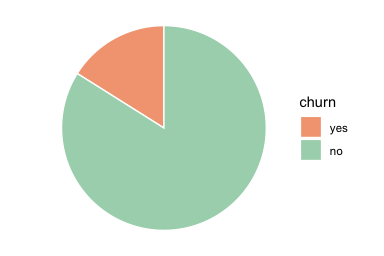

We begin by examining the distribution of the target feature churn, which indicates whether a customer has closed a credit card account. Understanding this distribution is important for assessing class balance, a factor that influences both model training and the interpretation of predictive performance. The bar plot and pie chart below summarize the proportion of customers who churned:

library(ggplot2)

# Bar plot

ggplot(data = churn, aes(x = churn, label = scales::percent(prop.table(after_stat(count))))) +

geom_bar(fill = c("#F4A582", "#A8D5BA")) +

geom_text(stat = "count", vjust = 0.4, size = 6)

# Pie chart

ggplot(churn, aes(x = 1, fill = churn)) +

geom_bar(width = 1) +

coord_polar(theta = "y") +

theme_void()

Both plots show that most customers remain active (churn = "no"), while only a small proportion (about 16.1 percent) have closed their accounts. The bar plot makes the class imbalance immediately visible and supports direct comparison of counts or proportions. The pie chart conveys the same information but is less effective for analytical comparison; it is included here primarily to illustrate alternative presentation styles for a binary outcome.

A simpler bar plot, without colours or percentage labels, can be created as follows:

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_bar(aes(x = churn))This basic version provides a quick overview of class counts, while the enhanced plot communicates relative proportions more clearly. Such refinements are particularly useful when presenting results to non-technical audiences.

Practice: Create a bar plot of the

genderfeature using ggplot2. Experiment with adding colour fills or percentage labels. This short exercise reinforces the structure of bar plots before examining relationships between categorical features.

Having established the overall distribution of the target variable, the next step is to explore how other categorical features vary across churn outcomes. These comparisons help identify customer segments and behavioral patterns that may be associated with elevated attrition risk.

Relationship Between Gender and Churn

Among the demographic features, gender provides a natural starting point for exploring whether customer retention behavior differs across broad population groups. Although gender is not typically a strong predictor of churn in financial services, examining it first establishes a useful baseline for comparison with more behaviorally driven features.

We note that, in this dataset, the gender feature is recorded as a binary category. This representation does not capture the full diversity of gender identities and excludes non-binary and LGBTQ+ identities. Any conclusions drawn from this feature should therefore be interpreted with caution, both analytically and ethically, as they reflect limitations of the available data rather than characteristics of the underlying population.

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_bar(aes(x = gender, fill = churn)) +

labs(x = "Gender", y = "Count", title = "Counts of Churn by Gender")

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_bar(aes(x = gender, fill = churn), position = "fill") +

labs(x = "Gender", y = "Proportion", title = "Proportion of Churn by Gender")

The left panel shows the number of churners and non-churners within each gender group, while the right panel displays the corresponding proportions. The proportional view facilitates comparison of churn rates across groups and reveals a slightly higher churn rate among female customers. The difference, however, is small and unlikely to be practically meaningful in isolation.

To examine this pattern more closely, we can inspect the corresponding contingency table:

addmargins(table(churn$churn, churn$gender,

dnn = c("Churn", "Gender")))

Gender

Churn female male Sum

yes 930 697 1627

no 4428 4072 8500

Sum 5358 4769 10127The table confirms the visual impression that the proportion of female customers who churn is marginally higher than that of male customers. At this stage, the analysis remains descriptive. Determining whether such a difference is statistically significant requires formal inference, which is introduced in Section 5.8.

From an exploratory perspective, this finding suggests that gender alone is not a strong differentiating feature for churn behavior. In practice, larger and more informative variation is typically associated with behavioral and financial indicators such as transaction activity, credit utilization, and customer service interactions. These features therefore tend to carry greater predictive value in churn modeling contexts.

Practice: Compute the churn rate separately for male and female customers using the

churndataset. Then create your own bar plot and compare it with the figures above. Based on the observed proportions, would you expect the difference in churn rates to be statistically significant? This question is revisited formally in Chapter 5.8, where the test for two proportions is introduced.

Relationship Between Card Category and Churn

Card type is one of the most informative service features in the churn dataset. The variable card_category places customers into four tiers: blue, silver, gold, and platinum. These categories reflect different benefit levels and often correspond to distinct customer segments.

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_bar(aes(x = card_category, fill = churn)) +

labs(x = "Card Category", y = "Count")

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_bar(aes(x = card_category, fill = churn), position = "fill") +

labs(x = "Card Category", y = "Proportion")

The left panel displays the number of churners and non-churners within each card tier. The right panel shows proportions within each tier. The distribution is highly imbalanced: more than 93 percent of customers hold a blue card, the entry-level option. This reflects typical product portfolios in retail banking, where most customers hold standard cards. Because the other categories are much smaller, differences across tiers must be interpreted with care.

addmargins(table(churn$churn, churn$card_category,

dnn = c("Churn", "Card Category")))

Card Category

Churn blue silver gold platinum Sum

yes 1519 82 21 5 1627

no 7917 473 95 15 8500

Sum 9436 555 116 20 10127The contingency table confirms the visual pattern. Churn rates are slightly higher among blue and silver cardholders and lower among customers with gold or platinum cards. Although modest, this difference suggests that customers with premium cards are more engaged and therefore less likely to close their accounts.

Because the silver, gold, and platinum groups are relatively small, analysts often combine similar categories to ensure adequate group sizes for Modeling. A common approach is to separate “blue” from “silver+” (a combined group of silver, gold, and platinum cardholders). This simplification reduces sparsity, stabilises estimates, and often produces clearer and more interpretable models.

Practice: Reclassify the card categories into two groups, “blue” and “silver+”, using the

fct_collapse()function from the forcats package (as in Section 3.10). Then recreate both bar plots and compare the patterns. Does the simplified version make the churn differences easier to see? Would this reclassification improve interpretability in a predictive model?

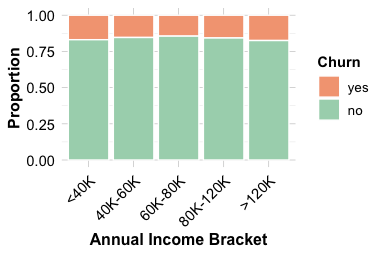

Relationship Between Income and Churn

Income level reflects purchasing power and financial stability, both of which may influence a customer’s likelihood of closing a credit account. The feature income in the churn dataset includes five ordered categories, ranging from less than $40K to over $120K. Because missing values were imputed earlier, the feature now provides a complete and consistent basis for comparison.

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_bar(aes(x = income, fill = churn)) +

labs(x = "Annual Income Bracket", y = "Count") +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_bar(aes(x = income, fill = churn), position = "fill") +

labs(x = "Annual Income Bracket", y = "Proportion") +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1))

The bar plots indicate a gradual decline in churn as income increases. Customers in the lowest bracket (less than $40K) churn slightly more often than those in higher brackets, while customers earning over $120K show the lowest churn rates. Although the trend is modest, it suggests that higher-income customers maintain more stable account relationships. To examine this pattern more closely, we can inspect the corresponding contingency table:

addmargins(table(churn$churn, churn$income,

dnn = c("Churn", "Income")))

Income

Churn <40K 40K-60K 60K-80K 80K-120K >120K Sum

yes 677 310 227 271 142 1627

no 3327 1705 1345 1453 670 8500

Sum 4004 2015 1572 1724 812 10127The contingency table supports this observation. Lower-income customers may be more sensitive to service fees or constrained credit limits, while higher-income customers typically exhibit more consistent spending patterns and longer account tenure.

From an analytical perspective, income provides a weak yet interpretable signal of churn behavior. Because the categories follow a natural progression, treating income as an ordered factor may be useful during Modeling.

Practice: Convert

incomeinto an ordered factor usingfactor(..., ordered = TRUE)and recreate the proportional bar plot. Does the plot change? Next, reorder the categories usingfct_relevel()and observe how the ordering affects readability. Small adjustments to factor ordering often make EDA plots easier to interpret.

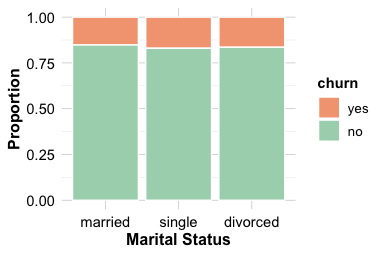

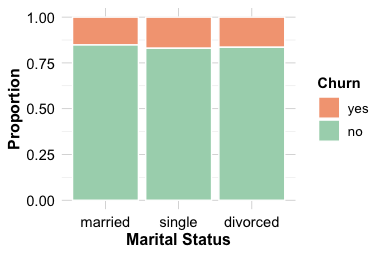

Relationship Between Marital Status and Churn

Marital status may influence financial behavior and account management, making it a useful demographic feature to explore in the context of churn. The marital feature in the churn dataset includes three categories (married, single, and divorced) which may reflect differences in household structure, shared responsibilities, or spending patterns.

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_bar(aes(x = marital, fill = churn)) +

labs(x = "Marital Status", y = "Count")

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_bar(aes(x = marital, fill = churn), position = "fill") +

labs(x = "Marital Status", y = "Proportion")

The count plot on the left shows that most customers are married, followed by single and divorced individuals. The proportional bar plot on the right highlights that single customers churn at a slightly higher rate than married or divorced customers. This difference is consistent but small, suggesting only a weak relationship between marital status and account closure.

addmargins(table(churn$churn, churn$marital,

dnn = c("Churn", "Marital Status")))

Marital Status

Churn married single divorced Sum

yes 767 727 133 1627

no 4277 3548 675 8500

Sum 5044 4275 808 10127The contingency table supports the visual impression. Although single customers exhibit marginally higher churn rates, the overall association between marital status and churn appears limited. Small behavioral differences may exist across household types, but marital status is unlikely to be a strong predictor of churn on its own.

From an analytical standpoint, this feature offers only minor explanatory value. Later sections will show that behavioral and financial indicators—including spending activity, utilization ratio, and customer-service interactions—provide more substantial insight into churn risk. Because both marital and churn are categorical variables, the Chi-square test introduced in Section 5.9 will formally assess whether the observed differences are statistically meaningful.

Practice: Examine whether

educationis associated with churn. Create bar plots for counts and proportions, inspect the contingency table, and consider whether any observed differences appear meaningful in practice. This exercise reinforces the workflow used for exploring categorical features.

4.5 Exploring Numerical Features

The churn dataset contains fourteen numerical features that describe customer behavior, credit management, and engagement with the bank. Examining these features helps us understand how customers differ in spending patterns, activity levels, financial capacity, and behavioral change, all of which are commonly associated with churn risk.

To keep the analysis focused and interpretable, we concentrate on five representative numerical features that capture key behavioral and financial dimensions of customer retention: contacts_count_12, transaction_amount_12, credit_limit, months_on_book, and ratio_amount_Q4_Q1. Together, these variables reflect customer interaction with the bank, overall engagement, financial strength, tenure, and recent behavioral trends. They provide a compact yet informative basis for exploring numerical patterns related to churn.

In the following subsections, we use summary statistics and visualizations to examine the distributions of these features and their relationships with customer churn, with the aim of identifying meaningful variation and potential signals for subsequent analysis.

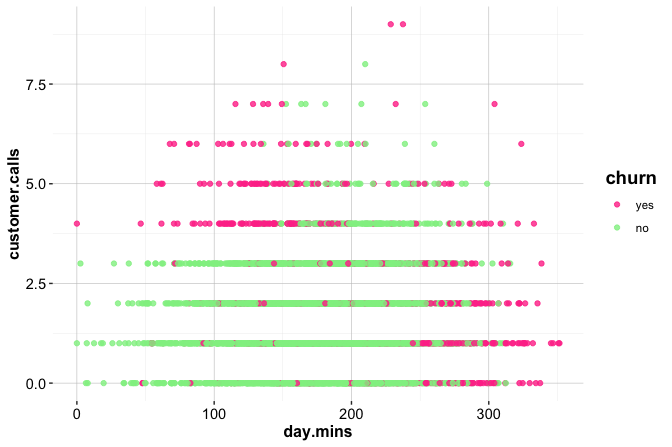

Customer Contacts and Churn

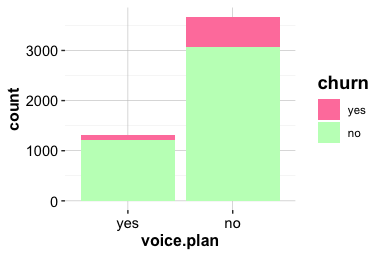

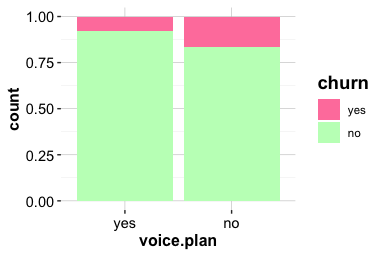

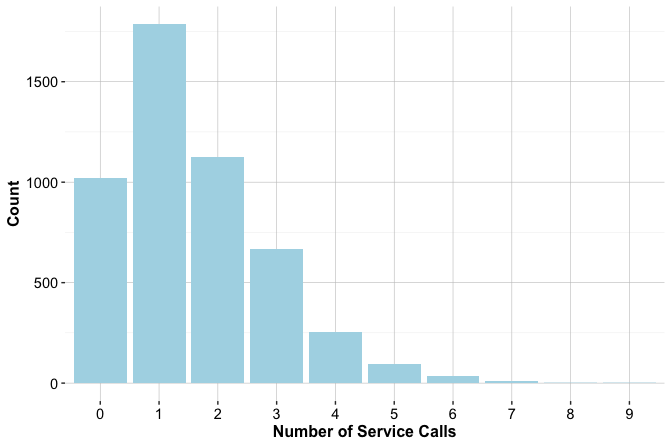

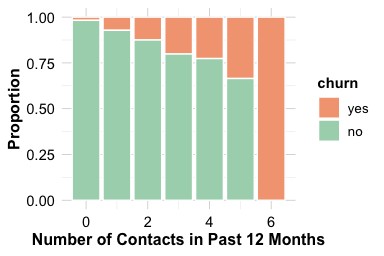

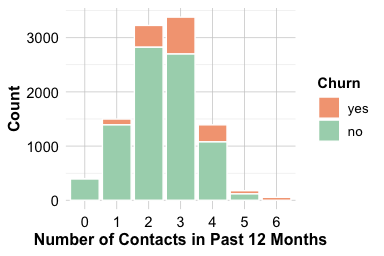

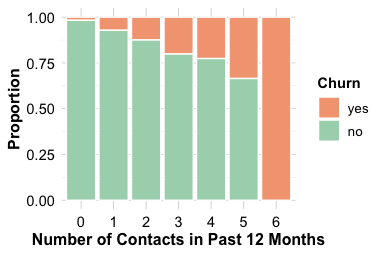

The number of customer service contacts in the past year (contacts_count_12) offers insight into customer engagement and potential dissatisfaction. This feature is a count variable with small integer values, making bar plots more appropriate than boxplots or density plots. Bar plots clearly display how frequently customers interacted with support and allow easy comparison between churned and active accounts.

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_bar(aes(x = contacts_count_12, fill = churn)) +

labs(x = "Number of Contacts in 12 Months", y = "Count")

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_bar(aes(x = contacts_count_12, fill = churn), position = "fill") +

labs(x = "Number of Contacts in 12 Months", y = "Proportion")

Both plots show that customers who contact customer service more frequently are more likely to churn. The increase is particularly noticeable for those with four or more interactions during the year. This pattern suggests that repeated service contacts may reflect concerns, dissatisfaction, or unresolved issues. From an analytical perspective, contacts_count_12 provides a clear behavioral signal: frequent contact is associated with elevated churn risk. Because it is easy to interpret and directly linked to customer experience, this feature often plays a meaningful role in churn Modeling and early-warning retention strategies.

Transaction Amount and Churn

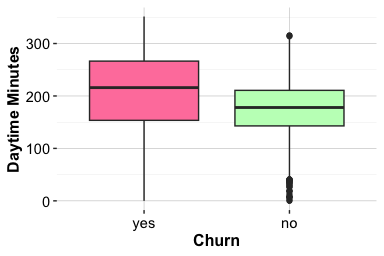

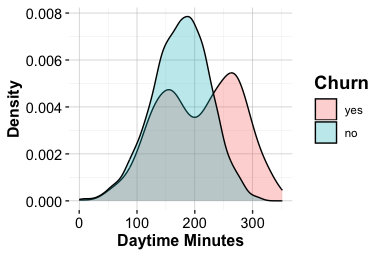

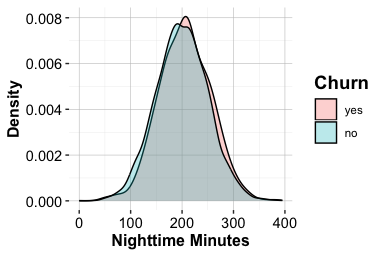

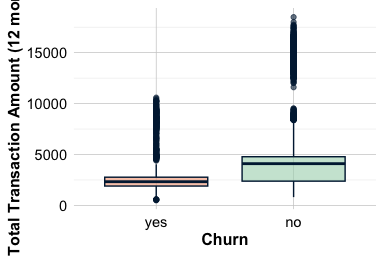

The total transaction amount over the past twelve months (transaction_amount_12) reflects how actively customers use their credit card. Higher spending is typically associated with regular engagement, whereas lower spending may indicate reduced usage or a shift toward alternative payment methods. Because this feature is continuous, we use boxplots and density plots to examine how its distribution differs between customers who churn and those who remain active.

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_boxplot(aes(x = churn, y = transaction_amount_12),

fill = c("#F4A582", "#A8D5BA")) +

labs(x = "Churn", y = "Total Transaction Amount")

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_density(aes(x = transaction_amount_12, fill = churn), alpha = 0.6) +

labs(x = "Total Transaction Amount", y = "Density")

The boxplot highlights differences in central tendency and spread, while the density plot provides a more detailed view of the distributional shape. Together, the plots show that customers who churn tend to have lower total transaction amounts and a narrower range of spending, suggesting more limited engagement over the year. In contrast, customers who remain active exhibit higher and more variable transaction volumes.

From an exploratory perspective, this pattern indicates that sustained reductions in spending are associated with an increased likelihood of churn. Such insights motivate closer monitoring of spending behavior and help identify customers whose engagement appears to be declining, although further analysis is required to assess predictive strength and causal relevance.

Practice: Recreate the density plot for

transaction_amount_12using a histogram instead. Experiment with different bin widths and compare the resulting plots. How sensitive are your conclusions to these choices? Which visualization would you use for exploratory analysis, and which for reporting results?

Credit Limit and Churn

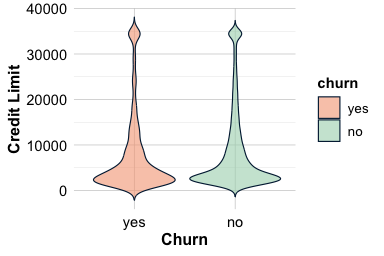

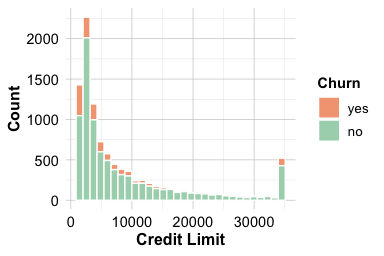

The total credit line assigned to a customer (credit_limit) reflects both financial capacity and the bank’s assessment of creditworthiness. Customers with higher credit limits are often more established or have demonstrated reliable repayment behavior, which may be associated with a lower likelihood of churn. Because credit limits vary substantially across customers, we use violin plots and histograms to examine both distributional shape and differences between churn groups.

ggplot(data = churn, aes(x = churn, y = credit_limit, fill = churn)) +

geom_violin(trim = FALSE) +

labs(x = "Churn", y = "Credit Limit")

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_histogram(aes(x = credit_limit, fill = churn)) +

labs(x = "Credit Limit", y = "Count")

The violin plot suggests that customers who churn tend to have lower credit limits on average, although the overlap between the two groups is substantial. The histogram provides additional insight into the overall distribution, revealing that most customers fall into a lower credit limit range, with a smaller group holding substantially higher limits. This pattern gives the appearance of two broad clusters, one concentrated below approximately $7,000 and another above $30,000, though this observation remains exploratory.

Taken together, the plots indicate a modest shift toward higher credit limits among customers who remain active, but the separation between groups is not pronounced. To assess whether the observed difference in average credit limits is statistically meaningful, we return to this comparison in Section 5.7, where we introduce formal hypothesis testing for numerical features.

From an exploratory standpoint, credit limit appears to be a weaker differentiating feature than transaction activity, but it still provides useful contextual information about customer profiles. Its primary value at this stage lies in complementing behavioral indicators rather than serving as a standalone signal of churn.

Practice: Create boxplots and density plots for

credit_limitstratified by churn status. Compare these with the violin plot and histogram shown in this section. How do the different visualizations influence your perception of group overlap and central tendency? Discuss which plots are most informative at this exploratory stage.

Months on Book and Churn

The feature months_on_book measures how long a customer has held their credit card account. Tenure often reflects relationship stability, accumulated benefits, and familiarity with the service. Customers with longer histories typically show stronger loyalty, whereas newer customers may be more vulnerable to unmet expectations or early dissatisfaction.

# Violin and boxplot

ggplot(data = churn,

aes(x = churn, y = months_on_book, fill = churn)) +

geom_violin(alpha = 0.5, trim = TRUE) +

geom_boxplot(width = 0.15, fill = "white", outlier.shape = NA) +

labs(x = "Churn", y = "Months on Book") +

theme(legend.position = "none")

# Histogram

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_histogram(aes(x = months_on_book, fill = churn), bins = 20) +

labs(x = "Months on Book", y = "Count")

Both plots suggest that customers who churn tend to have slightly shorter tenures than those who remain active. The difference is not large, but it is consistent: the median tenure for churners is lower by a few months. The pronounced peak around 36 months likely reflects a cohort effect, possibly linked to a major acquisition campaign that occurred three years prior to the observation period.

From a business perspective, these patterns highlight the importance of early relationship management. Targeted onboarding, proactive engagement in the first year, and timely communication may help build loyalty among newer customers and reduce attrition during the initial stages of the customer lifecycle.

Practice: Create a density plot for

months_on_bookstratified by churn status. Compare these with the histogram shown in this section. How do the different visualizations influence your perception of group overlap and central tendency? Discuss which plots are most informative at this exploratory stage.

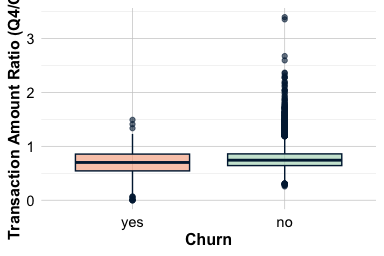

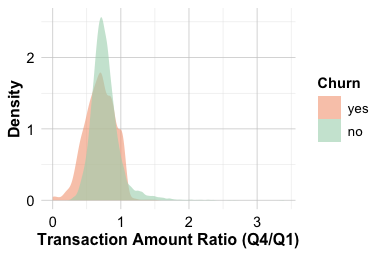

Ratio of Transaction Amount (Q4/Q1) and Churn

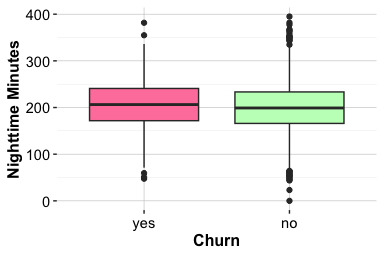

The feature ratio_amount_Q4_Q1 compares total spending in the fourth quarter with that in the first quarter. It captures how customer behavior changes over time and provides a temporal view of engagement. A ratio below 1 indicates that spending in Q4 was lower than in Q1, whereas a ratio above 1 reflects increased spending toward the end of the year.

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_boxplot(aes(x = churn, y = ratio_amount_Q4_Q1),

fill = c("#F4A582", "#A8D5BA")) +

labs(x = "Churn", y = "Transaction Amount Ratio")

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_density(aes(x = ratio_amount_Q4_Q1, fill = churn), alpha = 0.6) +

labs(x = "Transaction Amount Ratio", y = "Density")

The plots show that customers who churn tend to have lower Q4-to-Q1 ratios, indicating a reduction in spending toward the end of the year. Customers who remain active typically maintain or modestly increase their spending. This downward shift in activity may serve as an early sign of disengagement: gradual reductions in spending often precede account closure.

From a business perspective, monitoring quarterly spending patterns can help identify customers who may be at risk of churn. Seasonal incentives or targeted engagement campaigns aimed at customers with declining activity may help maintain their involvement and improve retention outcomes.

Practice: Repeat the analysis using features such as

ageandmonths_inactive. Compare the patterns you observe for churners and non-churners. How might these features contribute to predicting which customers are likely to remain active?

4.6 Exploring Multivariate Relationships

Univariate and pairwise analyses provide helpful context, but real-world customer behavior often arises from the interaction of multiple features. Examining these joint patterns is essential for identifying customer segments with distinct churn risks and for selecting features that add genuine value to predictive models.

We begin with a correlation analysis of the numerical features, which highlights pairs of variables that move together and helps detect redundancy. After establishing these relationships, we broaden the analysis to explore how behavioral, transactional, and demographic features interact. These multivariate views reveal usage patterns and customer profiles that are not visible through individual variables alone.

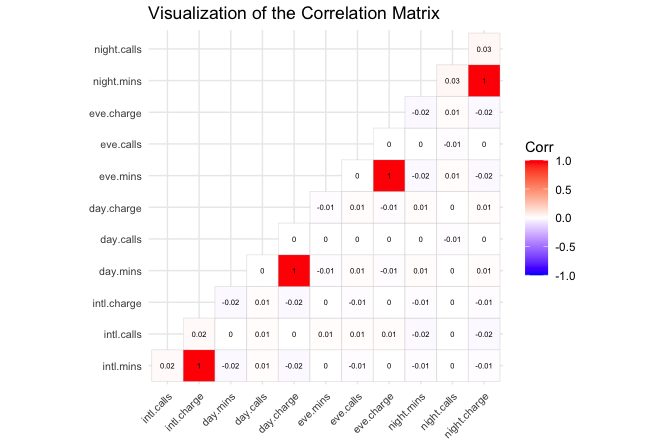

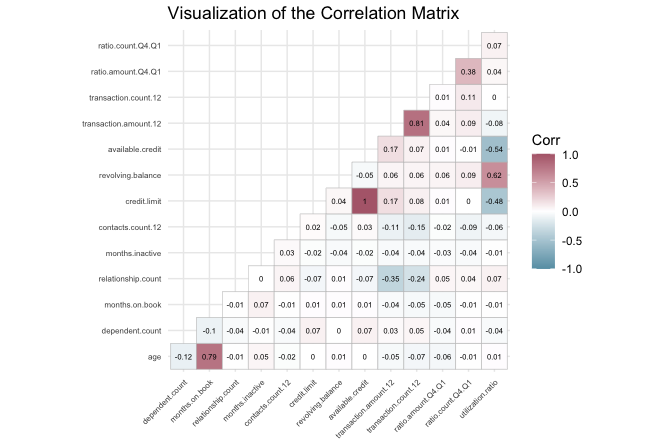

4.7 Assessing Correlation and Redundancy

Before examining more complex interactions among features, we assess how numerical variables relate to one another. Correlation analysis helps us identify features that may carry overlapping information or exhibit redundancy. Recognizing such relationships early simplifies subsequent modeling and reduces the risk of multicollinearity.

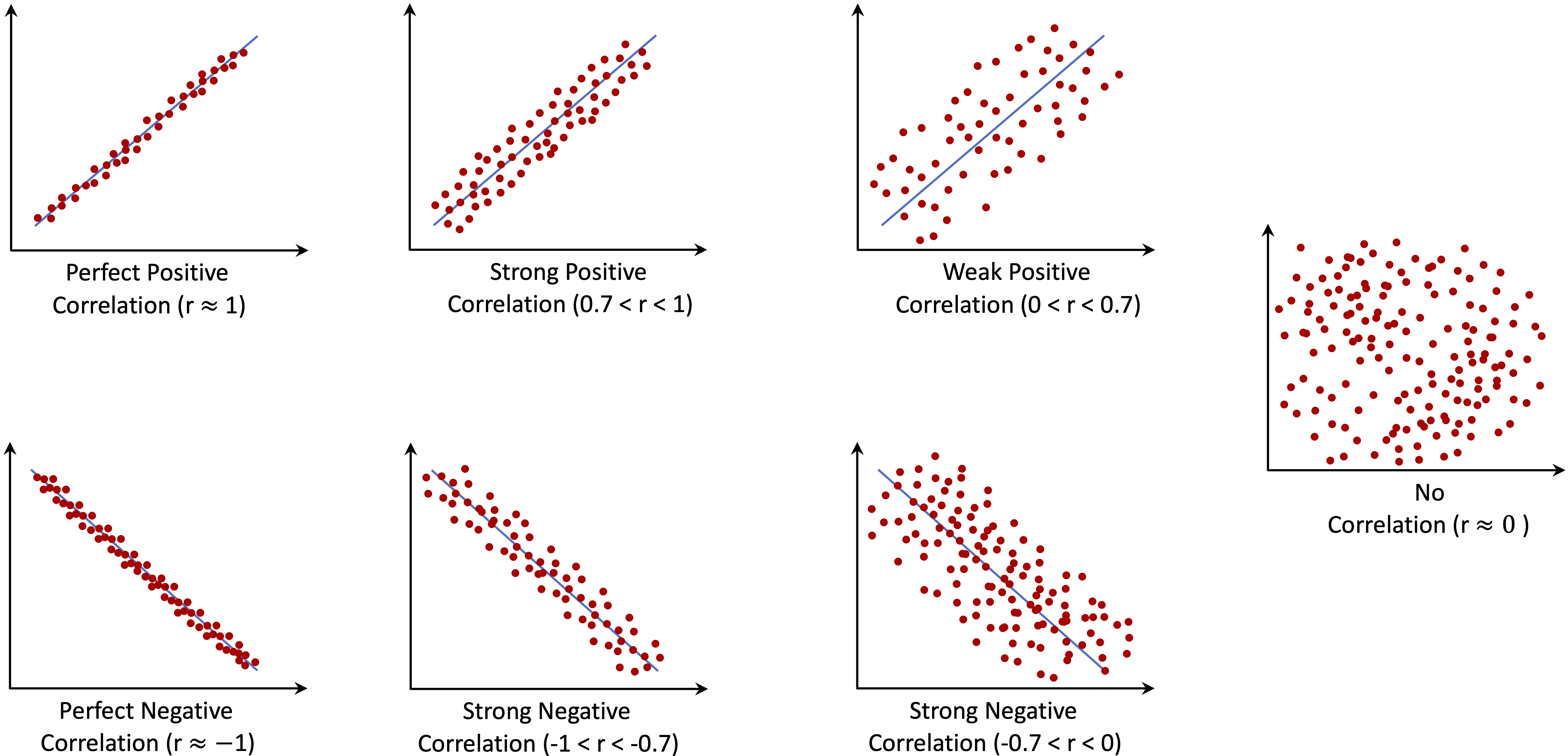

Correlation quantifies the degree to which two features move together. A positive correlation indicates that higher values of one feature tend to be associated with higher values of the other, whereas a negative correlation indicates an inverse relationship. The Pearson correlation coefficient, denoted by \(r\), summarizes this association on a scale from \(-1\) to \(1\). Values of \(r = 1\) and \(r = -1\) indicate perfect positive and negative linear relationships, respectively, while \(r = 0\) indicates no linear association.

We emphasize that correlation does not imply causation. For example, a strong positive correlation between customer service contacts and churn does not mean that contacting customer service causes customers to leave. Both behaviors may instead reflect an underlying factor, such as dissatisfaction with service.

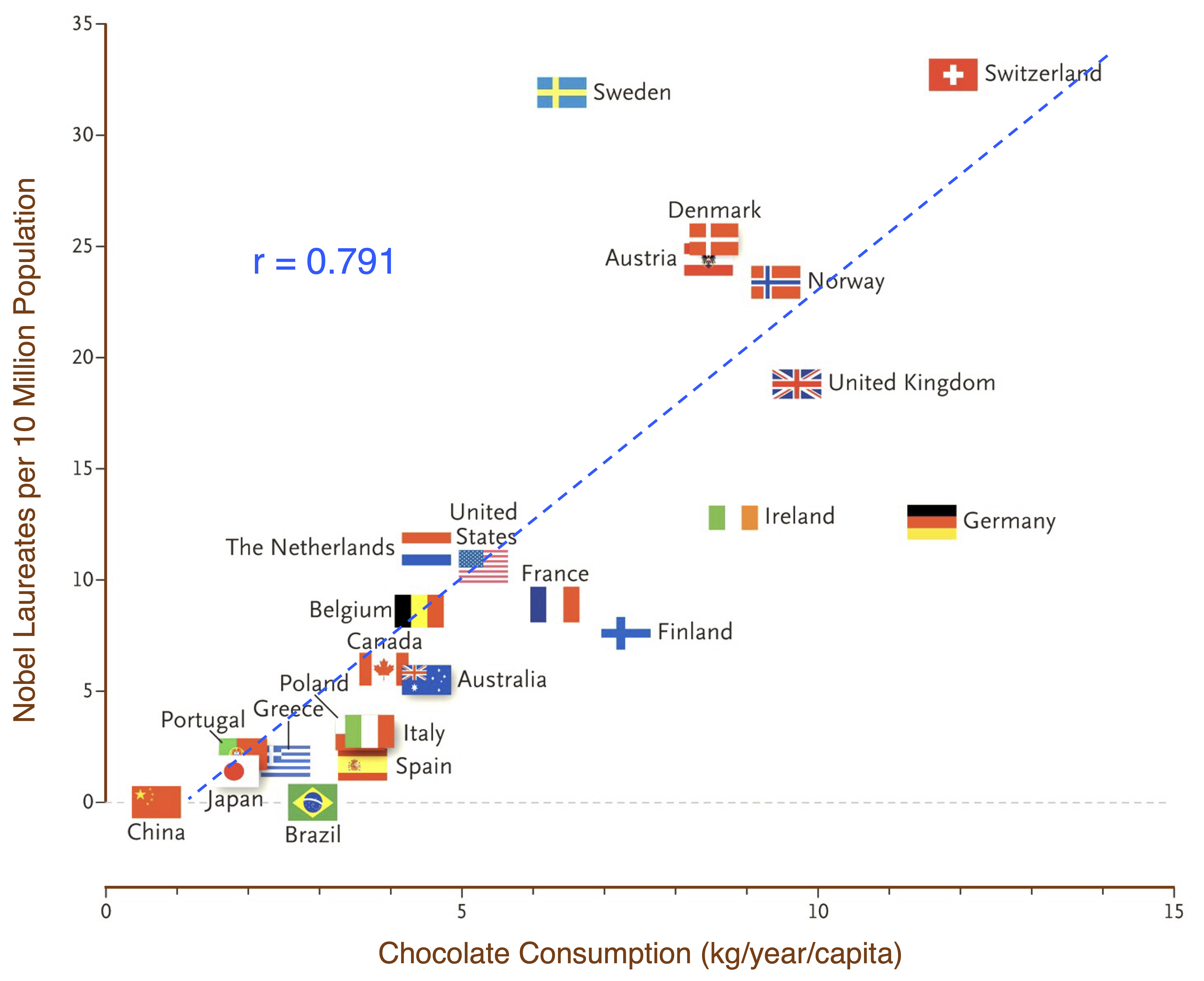

A well-known illustration of this principle is shown in Figure 4.3 which depicts a strong correlation between per-capita chocolate consumption and Nobel Prize wins across countries (Messerli 2012). While clearly not causal, the example highlights how correlations can arise through coincidence or shared underlying factors. Readers interested in causal reasoning may consult The Book of Why by Judea Pearl and Dana Mackenzie (2018) for an accessible introduction.

Returning to the churn dataset, we compute and visualise the correlation matrix for all numerical features using a heatmap. This overview helps us detect redundant or closely related variables before proceeding to modeling.

library(ggcorrplot)

numeric_features = c("age", "dependent_count", "months_on_book",

"relationship_count", "months_inactive", "contacts_count_12",

"credit_limit", "revolving_balance", "available_credit",

"transaction_amount_12", "transaction_count_12",

"ratio_amount_Q4_Q1", "ratio_count_Q4_Q1", "utilization_ratio")

cor_matrix = cor(churn[, numeric_features])

ggcorrplot(cor_matrix, type = "lower", lab = TRUE, lab_size = 1.7, tl.cex = 6,

colors = c("#699fb3", "white", "#b3697a"),

title = "Visualization of the Correlation Matrix") +

theme(plot.title = element_text(size = 10, face = "plain"),

legend.title = element_text(size = 7),

legend.text = element_text(size = 6))

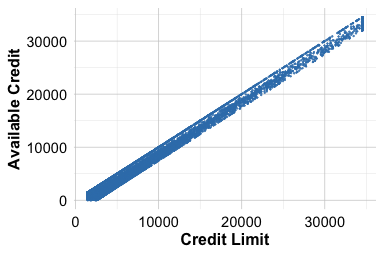

The heatmap shows that most numerical features are only weakly or moderately correlated, suggesting that they capture distinct behavioral dimensions. One notable exception is the perfect correlation (\(r = 1\)) between credit_limit and available_credit, indicating that one feature is mathematically derived from the other. Including both in a model would therefore introduce redundancy without adding new information. This relationship is illustrated in the following scatter plots:

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_point(aes(x = credit_limit, y = available_credit), size = 0.1) +

labs(x = "Credit Limit", y = "Available Credit")

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_point(aes(x = credit_limit - revolving_balance,

y = available_credit), size = 0.1) +

labs(x = "Credit Limit - Revolving Balance", y = "Available Credit")

The first plot shows the exact linear relationship between credit_limit and available_credit. The second confirms that available_credit is effectively equal to credit_limit - revolving_balance, explaining the observed redundancy.

As an optional exploration, we can examine the joint structure of these three features using a three-dimensional scatter plot. The plotly package enables interactive rotation and zooming, which can make this linear dependency especially apparent. This visualization is available in HTML output or interactive environments such as RStudio, but it does not render in the PDF version of this book.

library(plotly)

plot_ly(

data = churn,

x = ~credit_limit,

y = ~available_credit,

z = ~revolving_balance,

color = ~churn,

colors = c("#F4A582", "#A8D5BA"),

type = "scatter3d",

mode = "markers",

marker = list(size = 1)

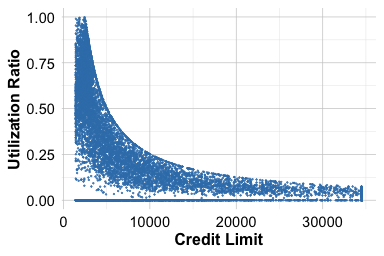

)A similar relationship appears between utilization_ratio, revolving_balance, and credit_limit. Because the utilization ratio is defined as revolving_balance / credit_limit, it does not introduce new information but provides a normalized view of credit usage. Depending on the modeling objective, we may retain the ratio for interpretability or keep its component features for greater flexibility.

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_point(aes(x = credit_limit, y = utilization_ratio), size = 0.1) +

labs(x = "Credit Limit", y = "utilization Ratio")

ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_point(aes(x = revolving_balance/credit_limit,

y = utilization_ratio), size = 0.1) +

labs(x = "Revolving Balance / Credit Limit", y = "utilization Ratio")

Practice: Create a three-dimensional scatter plot using

credit_limit,revolving_balance, andutilization_ratio. Because these features are mathematically linked, the points should lie close to a plane. Use plotly to explore the structure interactively. Rotate the plot and examine how the features relate. Does the three-dimensional view make the redundancy among these features more visually apparent?

Identifying redundant or highly correlated features provides a clearer foundation for multivariate exploration. After consolidating or removing derived variables, the remaining numerical features offer complementary perspectives on customer behavior. In the next subsection, we examine how key features interact, beginning with joint patterns in transaction amount and transaction frequency, to uncover usage dynamics that are not visible from individual features alone.

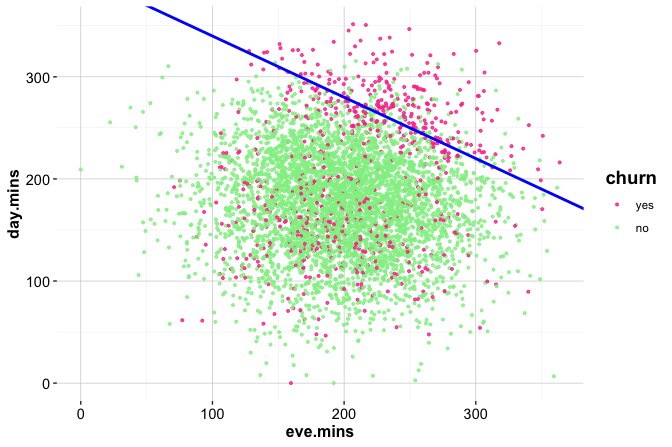

4.7.1 Joint Patterns in Transaction Amount and Count

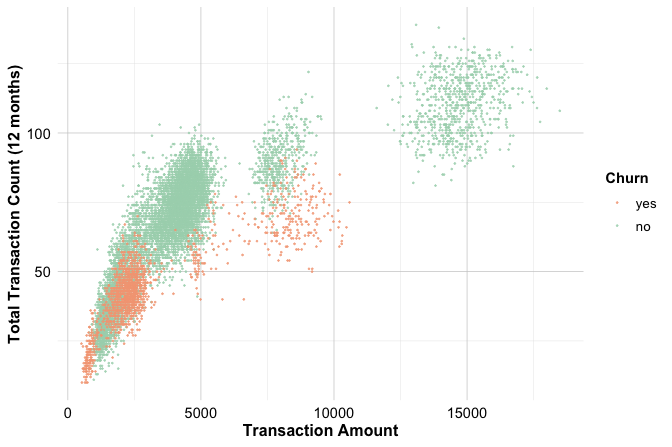

Transaction activity has two complementary dimensions: how much customers spend and how frequently they use their card. The features transaction_amount_12 and transaction_count_12 capture these behaviors over a twelve-month period. Examining them jointly provides insight into usage patterns that remain hidden in univariate analyses. A scatter plot augmented with marginal histograms is particularly useful here, as it simultaneously reveals the joint structure of the data and the marginal distributions of each feature.

The code below first constructs a base scatter plot using ggplot2 and then applies ggMarginal() from the ggExtra package to add histograms along the horizontal and vertical axes:

library(ggExtra)

# Base scatter plot

scatter_plot <- ggplot(data = churn) +

geom_point(aes(x = transaction_amount_12, y = transaction_count_12,

color = churn), size = 0.1, alpha = 0.7) +

labs(x = "Transaction Amount", y = "Total Transaction Count") +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

# Add marginal histograms

ggMarginal(scatter_plot, type = "histogram", groupColour = TRUE,

groupFill = TRUE, alpha = 0.3, size = 4)

The central scatter plot reveals a clear positive association: customers who spend more also tend to make more transactions. Most observations lie along a broad diagonal band representing moderate spending and activity, where churners and non-churners largely overlap. The marginal histograms complement this view by enabling a quick comparison of the individual distributions for both features across churn groups.

Beyond this general trend, the scatter plot suggests the presence of three broad usage segments: customers with low spending and few transactions, customers with moderate spending and moderate transaction counts, and customers with high spending and frequent transactions. Churners are predominantly concentrated in the low-activity segment, while the high-spending, high-usage segment contains very few churners.

Practice: Replace

type = "histogram"withtype = "density"inggMarginal()to add marginal density curves. Then recreate the scatter plot usingratio_amount_Q4_Q1on the horizontal axis instead oftransaction_amount_12. Which version makes differences between churn groups easier to detect?

To examine these patterns more closely, we focus on two illustrative subsets: customers with very low spending and customers with moderate spending but relatively few transactions. These subsets are extracted using the subset() function as follows:

sub_churn = subset(churn,

(transaction_amount_12 < 1000) |

((2000 < transaction_amount_12) &

(transaction_amount_12 < 3000) &

(transaction_count_12 < 52))

)

ggplot(data = sub_churn,

aes(x = churn,

label = scales::percent(prop.table(after_stat(count))))) +

geom_bar(fill = c("#F4A582", "#A8D5BA")) +

geom_text(stat = "count", vjust = 0.4, size = 6)

Within this subset, the proportion of churners is noticeably higher than in the full dataset. This reinforces the earlier observation that customers with low or inconsistent usage—particularly those who spend little and use their card infrequently—are at elevated risk of churn.

From a Modeling perspective, this example highlights the importance of feature interactions: neither transaction amount nor transaction count alone is sufficient to identify these customers, but their combination is informative. From a business perspective, low-activity customers represent a natural target for re-engagement strategies, such as personalized messaging or incentives designed to encourage more frequent card usage.

Card Category and Spending Patterns

The feature card_category divides customers into four product tiers (blue, silver, gold, and platinum). The feature transaction_amount_12 measures the total amount spent over the past twelve months. Examining these features together provides insight into how card tier relates to spending behavior. Because transaction_amount_12 is continuous and card_category is categorical, density plots are a natural choice for comparing entire distributions. They highlight differences in the shape, centre, and spread of spending among card tiers.

ggplot(data = churn,

aes(x = transaction_amount_12, fill = card_category)) +

geom_density(alpha = 0.5) +

labs(x = "Total Transaction Amount (12 months)",

y = "Density",

fill = "Card Category") +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("#1E90FF", "gray30", "#FFD700", "#BFC7CE"))

The density curves show a clear gradient across tiers: customers with gold and platinum cards tend to have noticeably higher transaction amounts. Their curves are shifted to the right relative to those of blue and silver cardholders. Blue card customers, who constitute more than 90 percent of the entire customer base, display a broader distribution concentrated in the lower and middle spending ranges. Although this imbalance affects how prominent each curve appears, the underlying pattern remains consistent: higher-tier cards are associated with greater spending activity.

From a business perspective, this relationship is intuitive. Premium cardholders typically receive enhanced benefits, rewards, or services, and they often belong to customer segments with higher financial engagement. Blue cardholders, by contrast, form a mixed group ranging from highly active customers to those who use their card only occasionally. These observations can guide differentiated retention and marketing strategies—for example, offering targeted upgrades to high-spending blue cardholders or designing tailored benefits to encourage greater engagement among lower-activity segments.

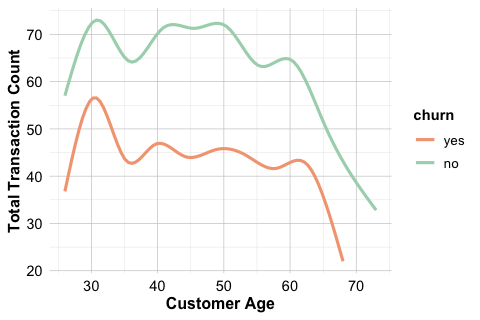

4.7.2 Transaction Analysis by Age

Age is an important demographic factor that can shape financial behavior, spending patterns, and overall engagement with credit products. In the churn dataset, examining how transaction activity varies across age helps determine whether younger and older customers display different usage profiles that might influence their likelihood of churn. Because individual observations form a dense cloud, we use smoothed trend lines to highlight the overall relationship between age and transaction activity.

# Total Transaction Amount for last 12 months by Age

ggplot(data = churn,

aes(x = age, y = transaction_amount_12, color = churn)) +

geom_smooth(se = FALSE, linewidth = 1.1, alpha = 0.9) +

labs(x = "Customer Age", y = "Total Transaction Amount")

# Total Transaction Count for last 12 months by Age

ggplot(data = churn,

aes(x = age, y = transaction_count_12, color = churn)) +

geom_smooth(se = FALSE, linewidth = 1.1, alpha = 0.9) +

labs(x = "Customer Age", y = "Total Transaction Count")

The curves indicate that both spending and transaction frequency tend to decline with age. Younger customers generally make more purchases and spend larger amounts, whereas older customers show lower and more stable levels of activity. There is a slight separation between churners and non-churners at younger ages: highly active younger customers appear somewhat more likely to churn, though the difference is modest.

These patterns emphasize that age alone does not determine churn. Instead, demographic characteristics interact with behavioral indicators to shape retention dynamics. Considering age jointly with measures of spending, engagement, and credit usage provides a more complete picture of customer behavior than any single feature on its own.

4.8 Summary of Exploratory Findings

The exploratory analysis of the churn dataset provides a multifaceted view of customer behavior and the factors associated with churn. By examining categorical features, numerical features, and their interactions, several consistent patterns emerge that are relevant for understanding and Modeling customer attrition.

Demographic characteristics show only weak associations with churn. Gender and marital status exhibit small differences in churn rates, and education and income levels display modest variation once other factors are considered. These variables may provide supporting context in Modeling but do not appear to be primary drivers of account closure. In contrast, service-related characteristics such as card category and income bracket offer clearer signals. Customers with higher-tier cards and those in higher income groups churn less often, suggesting that perceived value and financial capacity contribute to account stability.

The numerical features reveal stronger and more actionable patterns. Customers who contact customer service frequently, particularly four or more times within a year, churn at higher rates. This suggests that repeated service interactions may reflect dissatisfaction or unresolved problems. Spending activity, measured by total transaction amount over twelve months, shows a similarly strong relationship with retention. Active customers display higher and more varied spending, whereas churners typically have substantially lower transaction volumes. Declines in spending may therefore serve as early indicators of disengagement.

Credit-related features add further insight. Customers with lower credit limits are somewhat more likely to leave, while those with higher limits tend to remain active. This pattern may relate to differences in financial standing or to perceived benefits associated with higher credit availability. Tenure shows a modest but consistent relationship: customers with longer account histories are slightly less likely to churn, indicating that new customers may require additional support during the early stages of their relationship with the bank. The ratio of fourth-quarter to first-quarter spending highlights behavioral change over time. Churners often show declining spending in the later part of the year, whereas active customers tend to maintain or increase their usage. This dynamic measure is particularly useful for detecting emerging signs of disengagement.

Multivariate exploration deepens these insights. Joint analysis of transaction amount and transaction count shows that customers who both spend little and use their card infrequently have elevated churn rates. This relationship does not emerge as clearly from the individual features and demonstrates the importance of considering interactions. Combining card category with transaction amount reveals that higher-tier cardholders tend to spend more and churn less, while blue cardholders represent a more heterogeneous group that includes many low-activity accounts. Analysis across age groups shows that younger customers generally spend more and complete more transactions but experience slightly higher churn rates than older customers with comparable activity levels. This aligns with broader evidence that younger customers are more willing to switch providers.

The correlation analysis identifies a few redundant features. Available credit is determined by subtracting revolving balance from the credit limit, and the utilization ratio is calculated from revolving balance and credit limit. These relationships indicate that the derived features do not contain additional information beyond their components. For Modeling, it is often preferable to retain either the raw components or the ratio, depending on the analytical objective, rather than all three. Removing such redundant variables simplifies the feature set and reduces the risk of multicollinearity.

Overall, the exploratory analysis shows that churn is more closely associated with behavioral and financial indicators, such as spending activity, credit usage, and service interactions, than with demographic variables alone. Together, these findings provide a clear empirical foundation for the statistical inference and predictive Modeling in the chapters that follow. Several of the patterns identified here will be examined formally in Chapter 5 using hypothesis tests to assess whether these observed differences reflect wider population-level effects.

4.9 Chapter Summary and Takeaways

This chapter introduced exploratory data analysis as a practical and systematic step in the data science workflow. Using the churn dataset, we demonstrated how graphical and numerical techniques can be used to understand data structure, detect data quality issues, and develop initial hypotheses about customer behavior that guide subsequent analysis.

The analysis began with an overview of the dataset and an initial preparation step, during which missing values encoded as "unknown" were identified and resolved. Ensuring that features were clean and correctly typed provided a reliable foundation for exploration. We then examined categorical variables such as gender, education, marital status, income, and card type to characterise customer profiles, followed by numerical features related to credit limits, transaction activity, and utilization.

Several consistent relationships emerged from this exploratory analysis. Customers with smaller credit limits, higher utilization ratios, or frequent customer service interactions were more likely to churn. In contrast, customers with higher transaction amounts and lower utilization tended to remain active. These patterns illustrate how EDA can surface potentially important explanatory features before any formal Modeling is undertaken.

Multivariate exploration further revealed that churn behavior is shaped by combinations of features rather than isolated characteristics. Joint patterns in transaction amount and transaction count, associations between card category and spending, and links between age and financial activity showed how behavioral, financial, and demographic factors interact to influence customer retention.

The chapter also highlighted the importance of identifying redundant features. For example, available credit and utilization ratio were found to be deterministically related to other variables in the dataset. recognizing such redundancy simplifies later Modeling steps and improves interpretability.

Taken together, the examples in this chapter illustrate three guiding principles for effective exploratory analysis. First, graphical and numerical summaries are most informative when used together. Second, careful attention to data quality, including missing values and redundant features, is essential for reliable conclusions. Third, exploratory analysis is not merely descriptive. It provides direction for statistical inference and predictive Modeling by revealing patterns that merit further investigation.

The insights developed here form the empirical foundation for the next stage of the analysis. Chapter 5 introduces the tools of statistical inference, which allow us to formalise uncertainty, quantify relationships, and test hypotheses suggested by the exploratory findings.

4.10 Exercises

These exercises reinforce the main ideas of the chapter, progressing from conceptual questions to applied analysis with the churn_mlc and bank datasets, and concluding with integrative challenges.

Conceptual Questions

Why is exploratory data analysis essential before building predictive models? What risks might arise if this step is skipped?

If a feature does not show a clear relationship with the target during EDA, should it be excluded from modeling? Consider potential interactions, hidden effects, and the role of feature selection.

What does it mean for two features to be correlated? Explain the direction and strength of correlation, and contrast correlation with causation using an example.

How can correlated predictors be detected and addressed during EDA? Describe how this improves model performance and interpretability.

What are the potential consequences of including highly correlated features in a predictive model? Discuss the effects on accuracy, interpretability, and model stability.

Is it always advisable to remove one of two correlated predictors? Under what circumstances might keeping both be justified?

For each of the following methods—histograms, box plots, density plots, scatter plots, summary statistics, correlation matrices, contingency tables, and bar plots—indicate whether it applies to categorical data, numerical data, or both. Briefly describe its role in EDA.

A bank observes that customers with high credit utilization and frequent customer service interactions are more likely to close their accounts. What actions could the bank take in response, and how might this guide retention strategy?

Suppose several pairs of features in a dataset have high correlation (for example, \(r > 0.9\)). How would you handle this to ensure robust and interpretable modeling?

Why is it important to consider both statistical and practical relevance when evaluating correlations? Provide an example of a statistically strong but practically weak correlation.

Why is it important to investigate multivariate relationships in EDA? Describe a case where an interaction between two features reveals a pattern that univariate analysis would miss.

How does data visualization support EDA? Provide two specific examples where visual tools reveal insights that summary statistics might obscure.

Suppose you discover that customers with both high credit utilization and frequent service calls are more likely to churn. What business strategies might be informed by this finding?

What are some common causes of outliers in data? How would you decide whether to retain, modify, or exclude an outlier?

Why is it important to address missing values during EDA? Discuss strategies for handling missing data and when each might be appropriate.

Hands-On Practice: Exploring the churn_mlc Dataset

The churn_mlc dataset from the R package liver contains information on customer behavior and service usage in a telecommunications company. The goal is to study patterns associated with customer churn, defined as whether a customer leaves the service. The dataset was introduced earlier in this chapter and will be used again in later chapters, including the classification case study in Chapter 10. Additional details are available at https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/liver/refman/liver.html. To load and inspect the dataset:

library(liver)

data(churn_mlc)

str(churn_mlc)Summarize the structure of the dataset and identify feature types. What information does this provide about the nature of the data?

Examine the target feature

churn. What proportion of customers have left the service?Explore the relationship between

intl_planandchurn. Use bar plots and contingency tables to describe what you find.Analyze the distribution of

customer_calls. Which values occur most frequently? What might this indicate about customer engagement or dissatisfaction?Investigate whether customers with higher

day_minsare more likely to churn. Use box plots or density plots to support your reasoning.Compute the correlation matrix for all numerical features. Which features show strong relationships, and which appear independent?

Summarize your main EDA findings. What patterns emerge that could be relevant for predicting churn?

Reflect on business implications. Which customer behaviors appear most strongly associated with churn, and how could these insights inform a retention strategy?

Hands-On Practice: Exploring the bank Dataset

The bank dataset from the R package liver contains data on direct marketing campaigns of a Portuguese bank. The objective is to predict whether a client subscribes to a term deposit. This dataset will be used for classification in the case study of Chapter 12. More details are available at https://rdrr.io/cran/liver/man/bank.html. To load and inspect the dataset:

library(liver)

data(bank)

str(bank)Summarize the structure and feature types. What does this reveal about the dataset?

Plot the target feature

deposit. What proportion of clients subscribed to a term deposit?Explore the features

default,housing, andloanusing bar plots and contingency tables. What patterns emerge?Visualize the distributions of numerical features using histograms and box plots. Note any skewness or unusual observations.

Identify outliers among numerical features. What strategies would you consider for handling them?

Compute and visualize correlations among numerical features. Which features are highly correlated, and how might this influence modeling decisions?

Summarize your main EDA observations. How would you present these results in a report?

Interpret your findings in business terms. What actionable conclusions could the bank draw from these patterns?

Examine whether higher values of

campaign(number of contacts) relate to greater subscription rates. Visualize and interpret.Propose one new feature that could improve model performance based on your EDA findings.

Investigate subscription rates by

month. Are some months more successful than others?Explore how

jobrelates todeposit. Which occupational groups have higher success rates?Analyze the joint impact of

educationandjobon subscription outcomes. What patterns do you observe?Examine whether the

durationof the last contact influences the likelihood of a positive outcome.Compare success rates across campaigns. What strategies might these differences suggest?

Challenge Problems

Create a concise one- or two-plot summary of an EDA finding from the

bankdataset. Focus on clarity and accessibility for a non-technical audience, using brief annotations to explain the insight.Using the

adultdataset, identify a subgroup likely to earn over $50K. Describe their characteristics and how you uncovered them through EDA.A feature appears weakly related to the target in univariate plots. Under what conditions could it still improve model accuracy?

Examine whether the proportion of

depositoutcomes differs bymaritalstatus orjobcategory. What hypotheses could you draw from these differences?Using the

adultdataset, identify predictors that may not contribute meaningfully to modeling. Justify your selections with evidence from EDA.

Self-Reflection

Reflect on what you have learned in this chapter. Consider the following questions as a guide.

How has exploratory data analysis changed your understanding of the dataset before modeling?

Which visualizations or summary techniques did you find most effective for revealing structure or patterns?

When exploring data, how do you balance curiosity-driven discovery with methodological discipline?

How can EDA findings influence later stages of the data science workflow, such as feature engineering, model selection, or evaluation?

In what ways did EDA help you detect issues of data quality, such as missing values or redundancy?